Photographs by Jenna Shea Mobley, Words by Bang Tran

About an hour north of Atlanta, on a small piece of land tucked away on Lake Lanier, John Wright scales a sourwood tree with youthful grace and speed. He looks down at us from the branches and laughs, “This is my tree. I grew up with this tree. I didn’t know it at first, but this is a sourwood. Doesn’t it just make sense?”

The sourwood and John lead kindred lives, having gotten taller and grown older on the same patch of family land for decades, and unsurprisingly, they also work together. John is in the honey business—he has been bringing the sweetness of the North Georgia mountains into Atlanta for many years now.

Not just any honey, though: John, founder of Bee Wild, brings mouth-watering, gourmet, and prized sourwood honey.

So yeah. It really does just make sense.

Sourwood honey is made by bees when they collect nectar from the sourwood tree, a tree that can be found from along wooded slopes of the Appalachians. From June to August, it blooms and produces loose, drooping clusters of small, white, bell-like flowers. During this short bloom period, beekeepers work hard to make sure that their bees are ready to produce pure sourwood honey. If the bees are out too early, they’ll collect nectar from other flowers (purity is a big deal). Too late, and the bees have missed precious time that they could’ve been collecting nectar from the sourwoods. Temperamental weather can also decrease honey yields, and this often leads to fluctuating supply of sourwood from year to year.

Short blooms, small range of the trees, and unpredictable weather all play a part in the price of sourwood. But it’s the flavor that makes it all worth it. People have compared it to gingerbread cookies, calling it spicy and deeply sweet with a tangy aftertaste. Some go as far as saying it’s the best honey in the world.

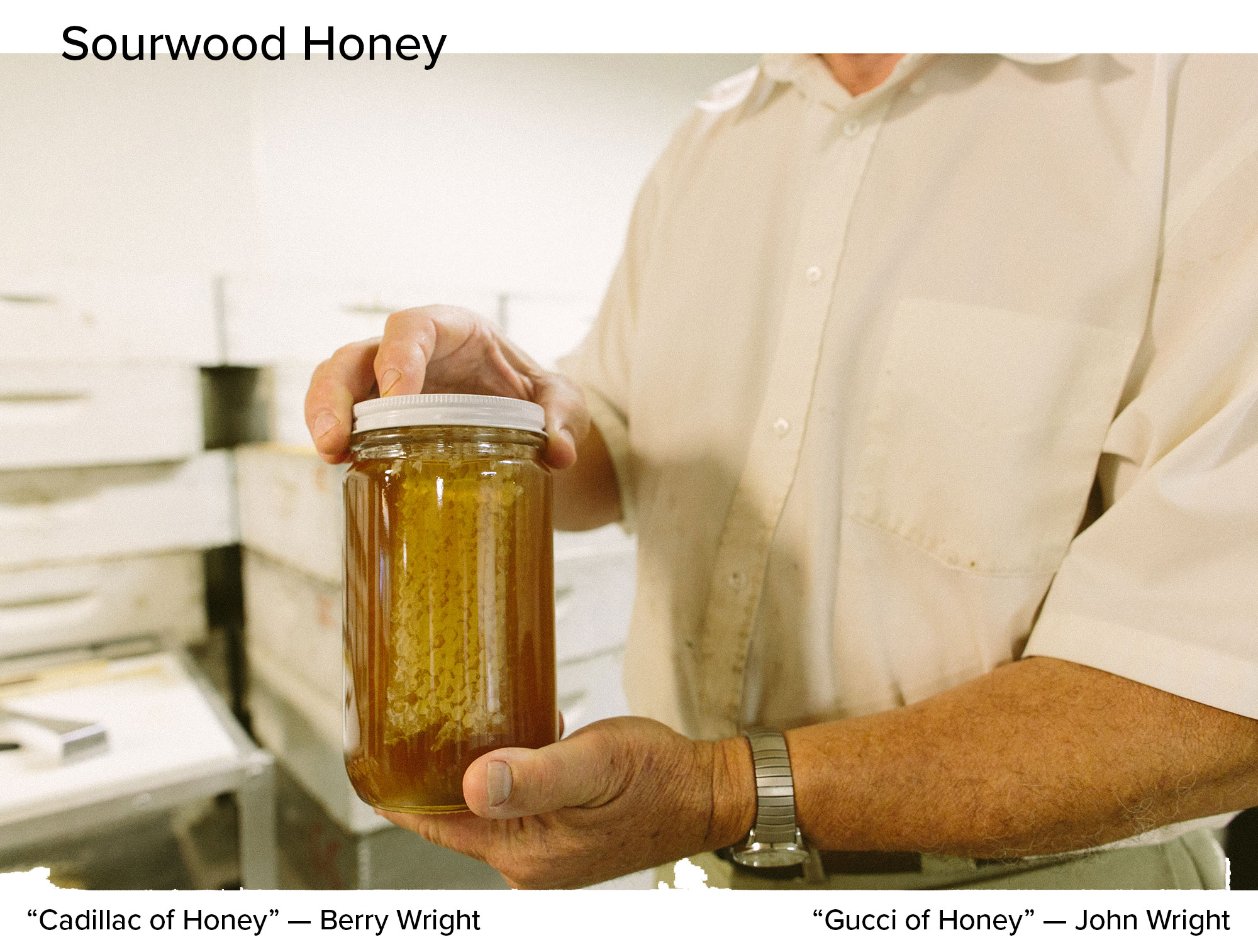

“Sourwood honey is what we call the Cadillac of All Honeys,” Berry Wright, John’s father, beams as he holds up a jar of precious sourwood honey.

Berry grew up helping his grandfather keep bees. When he was 10, his grandfather gave him 10 beehives to start off with. It began as a hobby, nothing too serious, but it eventually developed into a small-scale business. Now, he has 8 apiaries (a place where beehives are kept) in the North Georgia mountains: some in Habersham, three in Smithgall State Park, a few in Rabun County, and a couple others sprinkled around the mountains.

When I asked him what got him interested in beekeeping, he said, “I started because of the bees. The bees are in my blood.”

But beekeeping isn’t easy. It’s tough work. In the beginning, Berry was doing almost everything by hand—feeding hundreds of frames into the extractor by hand, slicing the caps off the honeycombs with a hot knife, lifting supers manually onto the truck’s trailer. In 1995, he purchased some equipment to help mechanize the honey processing and make it a little easier and more efficient. All that work is dependent on having honey in the first place, though.

“It’s hard. One year you’re way up and another you’re way down. It’s demoralizing when you have a year where you’ve invested your time and money into new queens, and you buy sugar to keep them alive in the wintertime, supplies to keep them from dying to mites… you lay out all this money and expect Mother Nature to cooperate for you to have a little extra honey during the flow. When you have a good year, you think, ‘I’m gonna make it, it’ll be great.’ Then the rain comes everyday and there’s no honey and you go out and feed the bees to keep them from starving, you think, ‘Why, why am I doing this? I’m spending all my money and time and I’ve got nothing to show for it.’ You learn to live with all that. You learn to live lean; you learn to live without some things”

When Berry starts talking about bees and honey, he doesn’t stop. He’ll talk about mites, moths, and other afflictions affecting bees. He’ll show you the difference between honey produced in higher-elevation versus honey produced in lower elevations and moisture content. He’ll tell you stories about that time he worked with other beekeepers to study the impact of Varroa destructor. He leads workshops and seminars, teaching the next generation the basics of beekeeping. You can hear in his voice the intensity and wisdom of someone who has devoted their entire life to their craft.

I ask Berry, “Is it all worth it?”

He lets out a small sigh, but smiles, “There’s a certain satisfaction on not being reliant on somebody else and working for yourself. At the same time you have to have a pretty good bit of discipline in order to keep it all together. You can’t just walk away from it—there’s always something to do. Always.”

By the time John was born, his father’s beekeeping business was already well underway. And while John grew up around the bees, it wasn’t always his intention to be a part of the honey business. He attended school for cosmetology, and spent some time working at high-end salons in Buckhead before returning to work with the family business.

But John created something for himself, too. While his father sells honey in North Georgia, John started his own business, Bee Wild, with the specific intention of bringing the Georgia mountain treasures into Atlanta. Berry sells honey in the country; John sells honey in the city.

“Honey is like fine wine—there’s so many varieties and so much complexity. People in the city want it, too. There’s a demand for it; there’s a demand for the way we do honey.”

John now employs 6 people to help with his business and sells at multiple different farmers markets and specialty food stores all around Atlanta. He’s constantly expanding and experimenting, creating honey-based products like lotions and figuring out other ways to incorporate honey into improving peoples’ everyday health. His plan is to keep spreading the good word of honey wherever he can.

Before we left, John showed us a pair of kiwi vines he planted when he was younger. The vines are now almost a decade old, thick, strong, and wild. They bear large, furry bunches of kiwis, bigger than any I’d seen growing in Georgia. He told us about how his family would gather in November to work together to harvest all the kiwis. He told us that, if you time it just right, the sunlight peeks through the foliage and creates a magical little sanctuary.

He told us that he’s letting the vines grow and extend all around the forest, spreading all over the trees, going wherever they please, clinging onto branches here and there, and bearing sweet fruit all along the way into the forest.

You can find Bee Wild at any of the following farmers markets: Grant Park Farmers Market, Ponce City Farmers Market, Westside Provisions Farmers Market, Decatur Farmers Market, and any of these retailers.